Architect of the digital age

A Primer on Continuous Delivery

25 February 2016

Continuous delivery is all about moving code to production as quickly as possible and with as much automation as possible. This reduces risk. If you’re able to automate everything from code check-in to production deployment, you’ve reached continuous deployment nirvana. That’s a stretch goal for most companies.

The Deployment Pipeline

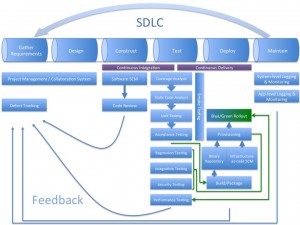

So you’re probably familiar with the IEEE SWEBOK’s definition of the software development lifecycle (SDLC). I’ve added a Deploy phase, as many people have, to illustrate what happens between Test and Maintain. Doing so better conforms to IEEE/EIA Standard 12207.0-1996. Some important takeaways:

-

One goal of using an agile methodology is shortening the feedback loop. If you’re pair programming, you’re literally receiving feedback while you’re coding. Each part of the pipeline contributes to the feedback loop. I’ve illustrated the feedback going into the formal defect tracking system, but many setups may be more informal. There isn’t necessarily a need to log a defect each time a new check-in fails a test. But failing that test is a signal to the software engineer that something may need attention - either the check-in or the test case.

-

I’ve separated the software and infrastructure configuration management (SCM) roles in the diagram, but in reality they should probably be the same system. Organizations that maintain separate software and infrastructure teams will have different repositories allowing role segmentation between the teams. Organizations embracing the Center of Excellence (CoE) model will likely have base infrastructure-as-code configurations stored in one repo managed by the CoE and each product team will extend those configurations with their application’s specific environment needs.

-

Binary repos like Artifactory or Nexus, from the software engineer’s perspective, are a relatively new phenomenon. But it’s old hat for system administrators who have traditionally used file shares and other less consistent methods to store your environment’s prerequisites, installers and executables.

-

Each box isn’t necessarily a discrete one-time activity. I’ve added some green arrows to try and show that the build process may happen multiple times. Other activities, like security and performance testing, can even become continuous processes during the Maintain phase.

-

I do not specify environments here. Ideally you are building and provisioning to one or more non-production environments and ensuring things (software and infrastructure) work correctly there before promoting to production. Someday you might be Facebook, in the meantime take your enterprise’s regulatory environment, and skill set, into perspective when determining the appropriate level of gating. You can take this generic pipeline and think in terms of “pipelines inside of pipelines” to account for your environments.

-

Finally, there are several boxes on this diagram that could and should stretch across more SDLC phases, and arrows that should go to more places (the SCM split I just mentioned for example). The arrows I’ve included illustrate one logical order - you should perform tests, etc., in whatever order makes sense for you. For simplification’s sake I’m just using this diagram to visualize DevOps processes and systems into a pipeline model. The more you can think of your deployment pipeline as a supply chain, the easier time you’ll have optimizing and operating it.

Deployment Models

One of the biggest benefits of moving to the cloud is the ability to deploy changes without negatively affecting users.

-

Traditional in-place upgrades: Take the necessary downtime and push to your existing servers using your configuration management tool of choice.

-

Containers like Docker bundle everything the app needs: all of its files, daemons, libraries, and dependencies. This simplifies deployment, while simultaneously increasing server utilization (as you can run multiple containers on one server), and enables microservices architectures. If you bind to different ports, you can run different versions of your software simultaneously. This allows you to release breaking changes while retaining backwards compatibility.

-

Rolling updates: If your environment has excess capacity (or you scale up prior to the upgrade), you can take a few servers down and update them, keeping a minimum number of them up to continue serving traffic. Rotate and repeat.

-

-

Rip and replace: Using infrastructure-as-code, create and test new server instances and once verified redirect users to them. This gives you the ability to patch your OS, update your environment prerequisites and your code all with little to no downtime. Two strategies:

-

Traditional red/black: Pick a time with as few users as possible (probably weekend or middle of the night) and cutover using DNS.

-

Blue/green: Gradually replace existing instances (blue) with the updated instances (green) using session-aware load balancing and DNS (increasing weight to the green instances). This gives you the quickest rollback in case of issues, in which case you just change the DNS weight preference back to blue. Once you confirm you’re up and running on green, use LB connection draining to minimize user impact. Whereas traditional blue/green involves equal-sized green and blue environments to start, “scale-out scale-in” blue/green deployments minimize costs by incrementing the green instances by 5% and then decreasing blue instances by 5% until complete. This is what companies like Netflix use.

-

If your environment is large enough, you will likely use some combination of these deployment models. For example, daily minor builds may use in-place while larger monthly builds use rip and replace so that the OS may be patched.

- Student Loan Bill Tracker

- The Anomaly Response Network

- The Mars Society

- Coca-Cola Scholars Foundation

- TechStars

- Leukemia & Lymphoma Society

- Cystic Fibrosis Foundation

- PRISM

- Free Bikes 4 Kidz

- Cincinnati Works

- Cincinnati Youth Collaborative

Reading:

Social